-Authors: Seun Bakare & Nkem Agunwa

This is the second of a two-part series. Part one titled: ‘Boiling earth, Hotter Battles: Examining Climate Change Conflict Connection’ is here.

The cost of conflict is extensive and long-lasting, encompassing immeasurable human, material, financial, and political consequences. While the human toll and economic devastation are often at the forefront, the environmental impacts of armed conflict are profound and cannot be overlooked.

For instance, when Iraqi forces deliberately set ablaze hundreds of oil fields in Kuwait during the Gulf war in 1991, it unleashed an environmental catastrophe. The plumes of thick smoke initially stretched out for 800 miles, choking the skies and contributing to widespread pollution. Furthermore, several million barrels of crude oil were intentionally pumped into the Persian Gulf, forming a slick that stretched 9 miles long. This devastated the land, marine life, and wildlife in the region.

As the oil-well fires raged on, an international coalition of firefighters worked for months in unimaginably challenging conditions to combat the infernos and mitigate the ecological and humanitarian fallout. This environmental devastation is a stark reminder of conflict’s profound and lasting consequences on the environment, extending far beyond the immediate battleground.

Till this day, the effects of the oil pollution still linger and more than 90% of the unprotected contaminated soil remains exposed in the environment. It has been estimated that the Gulf War’s oil fires in 1991 contributed to more than 2% of global fossil fuel CO2 emissions that year. This is just an estimate of the amount of pollution into the atmosphere from one war. More recent wars like the Russia-Ukraine war have also led to direct and indirect climate change effects. In the first seven months of the Russia-Ukraine war, the fighting released some 100 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, as well as the sabotage to the two Nord Stream pipelines in September 2022, which led to the biggest-ever point source release of methane – a potent warming gas. This was one of the consequences of the conflict on climate action, food supply and energy security. Additionally, the war has also caused widespread deforestation across Ukraine and damaged renewable energy systems: 90% of the country’s wind power and 50% of its solar energy capacity has been taken offline since the war began.

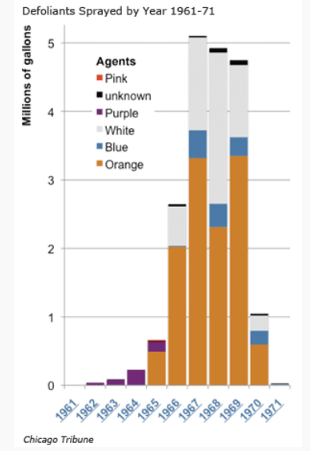

History has also shown how the use of chemical defoliants and mechanical clearance by the United States military in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos during the Vietnam War not only resulted in about 14-44% of Vietnam’s forest being lost but also contaminated water and habitation in numerous communities. A mixture of herbicides were sprayed by the U.S. military with the dual purpose of defoliating forest areas that might conceal Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces and destroy crops that would serve as a source of food for enemy fighters. As the chemicals were sprayed, areas across Bien Hoa, Phu Cat, and Da Nang were heavily contaminated with dioxin, the highly toxic and unintended by-product of the defoliant known as Agent Orange. By 1971, one-sixth of South Vietnam had been covered with 20 million gallons of herbicides, and as many as 4.8 million Vietnamese civilians had been exposed to the spray.

After the war ended, the Vietnamese (as well as American, Australian, and New Zealand veterans) became aware of the disturbing patterns of disease caused by exposure to dioxin. For people in affected Vietnamese communities, Agent Orange was (and still is) considered to be the cause of an abnormally high incidence of miscarriages, skin diseases, cancers, birth, and congenital defects, dating from the early 1960s to 1971.

It is estimated that as many as a million Vietnamese have disabilities that may be attributed to Agent Orange. According to the Vietnamese Association of Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA), till this day, there are over 3 million Vietnamese who have been affected with many still suffering from birth defects, disabilities and cancer. New cases are still appearing in the third generation to be born since the Vietnamese war ended. In 2019, efforts to begin the clean-up of Bien Hoa began, but the project is expected to take 10 years to complete and will cost up to $450 million.

Time and again, conflict has cast a long shadow over our environment, exacerbating pollution and hastening the pace of climate change. It leaves lasting scars on the earth and impedes nations’ ability to progress in addressing climate issues.

In 2021 the Biden administration committed to significantly reducing greenhouse emissions over this decade. However, the war in Ukraine has cast a pall over many such promises and has influenced U.S. climate policy in multifaceted ways. Notably, the U.S. Congress allocated considerably less to international climate funding than it had pledged, even as it earmarked billions of dollars for military assistance to Ukraine.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is undeniably a profound humanitarian crisis, marked by loss of life and the displacement of millions. However, its ripple effects extend far and wide. The war is heightening vulnerability to climate change, compounding security risks, complicating the transition to clean energy, and impeding collaborative international action on climate change. This confluence of crises underscores the complex interplay between geopolitics, climate, and the urgent need for a sustainable, peaceful world.

As world leaders grapple with mounting concerns about the war’s short-term and long-term consequences, the focus on tackling the climate crisis has waned. Urgent and ambitious climate action has been relegated down the priority list and media coverage. Regrettably, policymakers often relegate climate action as a “tomorrow’s issue” – something to be discussed later rather than an urgent matter requiring immediate attention. This delay in addressing climate change poses significant risks to our planet and future generations.

The Israel-Hamas conflict is a complex and deeply rooted geopolitical issue. It involves various actors and has significant humanitarian, environmental, and human rights implications. The use of certain weapons, such as white phosphorus, has been a subject of concern and debate, with human rights organizations raising questions about its impact on civilians and the environment. Injuries caused by white phosphorus are difficult to treat and often lead to long-term physical and psychological injury. Additionally, weapons like white phosphorus which cause incendiary effects spread easily and are often difficult to contain. International conventions and treaties like the Geneva Conventions, provide guidelines on using weapons in armed conflicts to protect civilians and minimize environmental harm.

The failure of many Middle Eastern and Western leaders to fulfil their commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement is a pressing concern. As we approach COP 28 in November, there is a growing fear that the ongoing conflicts, combined with regional tensions and interests, may disrupt climate negotiations and undermine efforts to achieve the ambitious climate action outlined in the agreement. It is evident that the cost of conflict, both in human and environmental terms, far exceeds the cost of pursuing peaceful solutions.

Amid these challenges, it is imperative to focus on how all stakeholders can collaborate to adapt to climate change and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities. The consequences of inaction are severe, as unchecked conflict and environmental degradation will ultimately affect us all. Climate change knows no borders and respects no conflicts. The imperative is clear, to secure a sustainable future: we must prioritise peace and collectively address the climate crisis.

Written by Seun Bakare & Nkem Agunwa

Climate Peace Alliance (CPA) is an international non-governmental organisation that works at the intersection of climate justice and violent conflicts. We are committed to addressing climate injustice and conflicts through peaceful and collaborative efforts. Recognising the importance of forging alliances among diverse stakeholders to create harmonious and sustainable communities, we work at the systems level of policy advocacy and grassroots mobilisation for action.

Seun Bakare is the Executive Director at CPA.

Nkem Agunwa is a journalist and activist.

One thought on “At What Cost: How Violent Conflict Worsens Climate Change Effects”

Conflict leads to unrecoverable damage to nature, vulnerable persons and livelihoods. Conflict displaces communities and draws a huge drift communities and nations that breaks the existing ties for development, social health and economic growth.

In the long run…we are all losing vis’ a vis’ conflicts and violence.